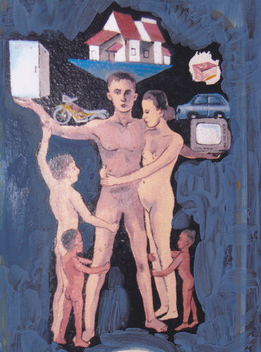

See this is the house we live them. To be a family home, it is a little eye blood spatter. Parents need to get a heavy load in order to maintain life in the tide. Dice up a job with the school and is not a burden on society. I just do not.

When a family is called the “habitable”, then it’s time to disease took the lives of persecuted parents with a family tired. I would rather be happy with that, I take it. To be admitted to hospital. Run out of money to gold. Have to ask you that. “Really enjoyed it”.

When a family is called the “habitable”, then it’s time to disease took the lives of persecuted parents with a family tired. I would rather be happy with that, I take it. To be admitted to hospital. Run out of money to gold. Have to ask you that. “Really enjoyed it”.

Reading the celebrity presenters Woody (2554) I interviewed many women Chulabhorn has one. He said that FA Women. I was born again. Would like to attain. Because life seemed so. Then he asked Woody’s. I was born again. Woody replied that it was because life is more fun. Young people are famous. Money Ood. Living like a sheer pleasure. Do not know what suffering is. However, this was not a happy one, as it still has a long reputation as it is slowly fading. Money furloughs. I’d asked for on the wilt disease was then asked if he wanted to. “I was born again.”

Buddha renounced all religious Find a real pleasure to do that will not happen again. He is also the fact that we were taught that. Do not do it. Life is uncertain too. Who’s idea was it to release. I had no idea that the sequences. It’s fun to imagine what life will be blessed. I was born to it. However, it is unlikely that a person will be born again. I may be a dog, a cat who knows.

U Nu’s strong desire for democracy for the nation and criticism of the dictatorship provide an important foundation for building liberty, equality and justice in a country that has been in disarray for decades.

All these facts relate to his early political life and are known among scholars of Myanmar’s history: they form the basis of interpretations of his formative years. Political life is indeed a major theme of the autobiography. U Nu details how he became interested in politics and then decided to become a politician, and what he did when he became the first prime minister of the young nation. In his political speech, he always said that: “In politics, don’t rely on arms, but just depend on public decisions!” (p.222). He clearly understood the importance of attending to the voices of the people rather than relying on political parties in the wielding of power. He brought the young nation together as one and also became the face of it in international fora during the early decades of the Cold War. U Nu also gives his frank opinions regarding political changes of the country after the coup in 1962. He mentioned that there were three types of enemies/opponents for democracy: (1) those in authority who are not willing to be accepted by the public, (2) those who are not, and never have been accepted by the public but rely on external elements and (3) those who have the arms and desire power (pp.355-356).

U Nu paying obeisance to the Buddha in 1961 ceremonies marking Vesak.

Besides dealing with aspects of his political life, the autobiography also reveals a different side of a man less known to the public. U Nu noted that he started to get interested in “Inn” (an esoteric religious belief system) as early as 1934; it is something he may have learnt about at an earlier stage in his life. He practiced this belief by reciting Parita suci (one of the important Buddhist ritual texts) and stated it was his preference over other rituals that used Buddhist prayer beads or observed eight or more Buddhist precepts. He firmly believed that this practice had completely changed his character and way of thinking. As such, he noted that when he was elected as prime minister he said to his colleagues that at first he would do it for only six months because he wanted to be a writer and to further practice the teaching of Buddha (p.215). During his service as prime minister, he claimed that he could gain self-control due to the teachings of Buddha.

Timely reading for the whole society of Myanmar

The autobiography is a timely reading for the whole society of Myanmar, especially for present day young people. Not only does it informs them about one of the great men the nation gave birth to, but it also inspires them to be courageous, despite some of the failures along the way, in hoping for a better future for the nation. U Nu’s strong desire for democracy for the nation and criticism of the dictatorship provide an important foundation for building liberty, equality and justice in a country that has been in disarray for decades. As such, this book may contribute to the political thinking of the current young generation who in the present climate of political transformation, can look back over modern Myanmar’s history to contextualize the changes taking place.

REVIEW: Hunger in Nayawak and Other Stories

Reviewed by Maria Ima Carmela Ariate

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 13 (March 2013). Monarchies in Southeast Asia

Hope Sabanpan-Yu (editor). 2012.

Hunger in Nayawak and Other Stories.

University of San Carlos Press and Cebuano Studies Center. 256 pages

Humanism in Lamberto G. Ceballos’ short stories

…Ang maikling kuwento ay sining, at ang sining – ang mataas na uri ng sining – ay higit sa paggagad sa panlabas na anyo ng realidad….Ito ay simbolikong representasyon ng realidad.

..The short story is an art, and this kind of art – the ‘high’ type of art – is more than an imitation of the external appearance of reality….This is a symbolic representation of reality. (Ricarte, Pedro. “Tungkol sa Maikling Kuwento,” Panitikan, III, II, Mayo 1967)

Hunger in Nayawak and other stories is a compilation of short stories that aim to “publicize the culture, history, and concerns of Cebu while entertaining the general readers.” The author, who is part of the Cebuano literary canon, is famous for his versatility, mass appeal, and for “producing community-themed work”. He was recognized by Bathalan-ong Halad sa Dagang, Inc-Cebu (Bathalad –Cebu) as the Writer of the Year in 2005. Four years later, his name was inscribed in the same institution’s hall of fame along with Rogelio Pono and Oliver Flores (Sabanpan-Yu, 2012: viii, x).

Aside from being published in magazines, these short stories have reaped awards and acclaim locally and nationally. “Tiggutom sa Nawak” (“Hunger in Nayawak”), from which the title of this anthology is derived, garnered the second place in the Don Carlos Palaca Memorial Awards for Cebuano Literature in 2003. Consequently, the Cebu City government honored his contribution to Cebuano language and culture by approving Resolution No. 03-1091 on September 10, 2003 (Sabanpan-Yu, 2012: viii).

Unparalleled mastery of the language

Lamberto Ceballos’ lush and vivid imagery of the Visayan countryside and his consistent and highly efficient use of the flashback to enhance characterization are the notable distinguishing features of his short stories. Written in Cebuano, Ceballos exhibits seemingly unparalleled mastery of the language as he creatively weaves his narratives and surprises the reader with unforeseen but logical twists in the plot.

2-books_thumb_medium250_178Translating the texts to English must have been challenging. Loban (1966:63) describes words as immensely important. How an individual classifies objects and experiences encountered and how he relates his perceptions are manifested in language. It is impressive for the translators to preserve local color and keep to the syntax of the original version. For instance, the dialogues, though in English, maintained the sprinkling of Cebuano exclamations such as ha, uy, and aw.

According to Melendrez-Cruz (1995), the humanism of the Filipino writers of the past lay in stories which appeal for the humane treatment of the disenfranchised and the unfortunate such as the physically and the mentally handicapped (Jose Panganiban’s “Vicenteng Bingi” 1 and Rogelio Sikat’s “Quentin”). Although predominantly regional, some of Ceballos’ short stories share the same outlook with these post-World War II liberal individualist writers with a particular focus on children.

Compassionate Storytelling

“The Road to darkness” narrates the story of the lives of underage laborers in Aduana, the port area near Carbon Market. Fidel, a fourteen-year old stevedore, and Samuel, a child who is slightly older, collect copra in the biggest warehouse by the dock. Samuel saved his life once but he was also caught stealing.

In exchange for their meager salary, they suffer inhuman working conditions and the violent treatment of a warehouseman. Pushed to the wall, they decide to join the other children in stealing copra. The warehouseman caught them in the act and shot Samuel who tried to escape. In revenge, since they were armed with knives, they stabbed the warehouseman. At the sound of the screeching police cars, they scampered away and Fidel found himself in grief beside Samuel’s lifeless body.

In his stories, Ceballos’ city is not the financial district or the location of the seat of political power. He chooses to set his plot in motion in the slums with some connectedness to the red light district and in pockets of isolation such as in “The real identity of Amadix”. Similar to romantic Filipino writers, Ceballos highlights how humanity physically and socially rises above the poverty and ugliness of the slums (Melendrez-Cruz, 1995: 160).

Poldo, the pickpocket with a pregnant wife, turns over a new leaf in “The new door”. He found permanent employment in The New Door Agency that opened its office near his shanty in the pier.

Further, the barrio (or village) is a venue for deep and meaningful relationships among men. “Hunger in Nayawak” opens with Mang Cardo cursing the person who robbed his bananas. The people of Nayawak were suffering from drought. Temoy, the suspect and his neighbor who lived uphill, did not have any source of income. The dry spell killed all the vegetables in his patch. To add, his wife, Dalay, had just given birth. For Mang Cardo, kind and gentle people like Temoy are not exempted from stealing when desperate. He intended to deal with Temoy the way he would with any other thief.

As he was walking back home from his friend’s hut on the hill, he found himself spying on Temoy and his family. His heart softened when he saw Temoy’s undernourished children and his wife who was trying to make the baby suckle. He also overheard Dalay’s sorrow upon learning that the couple had just fed their children with food that was stolen – food that was tainted with dishonesty. At the prodding of Dalay, Temoy headed out to Mang Cardo’s house to admit that he stole the bananas. He also intended to plead for his mercy and borrow corn kernels to mill at home for the nourishment of his family. Since Mang Cardo was just outside their abode, they were able to iron things out immediately. Mang Cardo also lent him three kilograms of corn kernels to mill. Implicitly, it wasn’t only the drought that was to end but the lack of empathy among the residents of Nayawak as well.

The barrio is also a venue for celebration. “There’s time for recompense” showcases a bicycle race that was part of Barangay Santa Monica’s fiesta celebration. “The burnt chapel” provides an account on how people have become more drawn towards the entertainment aspect of the fiesta, thus forgetting its religious essence.

Ceballos’ short stories symbolize reality as he puts forward characters that share common circumstances despite their unique individual experiences. Looking closely, there are men who are lovers, husbands, and sons as well as women who are lovers, wives, and daughters. And their experiences and emotions are part of a bigger humanity – a reflection of the human condition.

Reviewed by Maria Ima Carmela Ariate

Works cited

Loban, Walter. 1966. What language reveals. In James B. Macdonald and Robert R. Leeper, eds.Language and Meaning: Papers from The ACSD Tenth Curriculum Research Institute (pp. 63-73). Washington: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, NEA.

Melendrez-Cruz, Patricia. 1995. The Modern Pilipino Short Story (1946-1972): Consciousness and Counter-consciousness. In Elmer A. Ordonez, ed. Nationalist Literature: A Centennial Forum(148-173). 2005: Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press and PANULAT.

Sabanpan-Yu, Hope. 2013. Editor’s Preface. In Hope Sabanpan-Yu, ed. Hunger in Nayawak and other Stories (pp. vii-xvi). 2012: Cebu City: University of San Carlos Press and Cebuano Studies Center.

Tar Tei Sa Nay Thar (A child born on Saturday) Nyein Chan

BOOK REVIEW: Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 14 (September 2013).

Tar Tei Sa Nay Thar (A child born on Saturday)

Nga Doe Sar Pay (Yangon, Myanmar), 2012. The book is the autobiography of U Nu, a leading nationalist and political figure in 20thcentury Myanmar, and was originally written in 1969. It was first published in English in USA and India during 1969-1980, and in 1975, it was published in Burmese in India by Irrawaddy Publishing. It finally made print in Myanmar in September 2012 – right after the abolishment of media censorship by the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division under Ministry of Information. Since then, it has become a major bestseller in the country that led to a second printing in February 2013. Despite being an autobiography, the book is a reflection on Myanmar’s customs, religion and the historical events of his days. U Nu, also known as Thakin Nu, was Myanmar’s first prime minister under the 1947 constitution of the Union of Burma, a position he held for eight consecutive years and his political life forms a major narrative in it. As the author, he originally wrote it as a personal memoir for his family and descendants. It is a chronological composition of the events detailing his life, starting from the day he was born. For this reason, one of the undercurrents in the book is the author’s desire to show how he tried to reform himself over the duration of his life. It is worth noting that there is a strong belief in Myanmar that a child born on Saturday (Tar Tei Sa Nay Thar) has an extremely bad character and, his/her parents can face potentially big problems along the life span, and this finds itself poignantly reflected in the title itself. U Nu was a leading Burmese nationalist and political figure of the 20th century. U Nu was born on 25 May 1907 to U San Tun and Daw Saw Khin. He was at first named as Maung Tun Min, but it was later changed to Maung Nu before he went to primary school, as his father believed, in line with customs in Myanmar, that changing one’s name is an important point of transition in life. The name “Maung Tun Min” (“Tun Min” vernacularly means ‘King appears’) may have contributed to his son’s bad behavior and changing it to “Maung Nu” (“Nu” means ‘gentle/soft’), would hopefully support his future life. Nonetheless, U Nu noted countless examples of how he misbehaved as he grew up. In 1920, he participated in the first University Students Strike against British rule in Burma in which he noted how much he disliked how power was simply exercised to bully those who were in a weak position. In December 1921, he was involved in a peaceful strike against the Whyte committee which was set up by the British Colonial government and formed to investigate communal representation of the natives for the local parliament. In that strike, he threw a glass bottle at the ship that was carrying members of the committee and thus, was accused of obstructing them. In March 1922, he graduated from junior high school but became infamous among his friends as a womanizer due to a gonorrhea infection he picked up in 1923. This last event influenced his later life in the sense that he would try to control his sexual behavior. He also noted how after reading Cervante’s Don Quixote in 1924, he felt he shared many similarities with the protagonist in that he felt the urge to change his life: to not only to control his behavior, but also control his thoughts and speech. He also noted that the turning point in his early adult life was in March 1926, when he failed on the IA (Intermediate in Arts) exam and with that, he became interested in his conserving dignity from a religious point of view. Noticing a change in him, his father offered guidance according to the teachings of Buddha. He finally passed the IA exam the following year and earned his B.A. in 1929 from Rangoon University. Despite his desire to become a writer, U Nu soon enrolled on a LL.B. (Bachelor of Laws) program after graduation. However, three days after he started attending LL.B. course in May 1929, he was contacted by an uncle who invited him to visit Pantanaw, a town in the Ayeyarwady region, to become a local school teacher at a National High School. He took the job although he had no desire to become a school teacher at the age of 22. He noted how his stubborn character as a young man had caused him difficulties with the local education committee, but he managed to normally perform his teaching duties in class. It was during this time he met Ma Mya Yi, the sister of one of his best friends, whom he would later marry in 1931. In the autobiography, U Nu gave a detail description on how they met and started their family life together. In May 1933, he was appointed as the principal of the school. But, in 1934 he quit the job and resumed his LL.B. study, and it is a point that his political life began. In 1935, he was elected as the president of the Rangoon University Students Union (RUSU). Not long after that, both U Nu and Aung San (the Editor of the union magazine ‘O-wai’) were expelled from the university after an article published in the union magazine. The article, “Hell Hound Turned Loose,” was considered defamatory by the university principal with whom U Nu had some issues. U Nu made clear how he disliked the requirement imposed on students to salute the university principal, professors and lectures as he thought it was not a custom of the Burmese people. Their expulsion from the university sparked off the second University Students Strike in February 1936 that forced the university to drop the case and readmit them. In 1937, U Nu and Aung San became the members of the nationalist organization, Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association) – and with that, U Nu was known as Thakin (“Master”) Nu. On one occasion in 1938, with other members of the association, U Nu managed to sing the association’s song entitled the “Dobama Asiayone Thichin” (We Burmese) in the student hostel in front of the other students.